1,754 words

The Youth Criminal Justice Act (YCJA) came into force on April 1, 2003. This controversial law made significant changes to Canada's youth justice system. The YCJA emphasizes a reduction in the use of the formal court system and custody, community-based responses to youth crime, and better reintegration for young people who are incarcerated, among other things. The following is a mixed bag of issues, concerns and trends that have emerged in the past year, and that bear watching in the months and years to come.

Deaths in Custody

For some years now, child rights advocates have been concerned about deaths of young people in young offender custody or detention facilities.

In September, 1996, sixteen-year-old James Lonnee was beaten to death by another young person at the Wellington Detention Centre in Guelph, Ont. In July, 2001, fourteen-year-old Paola Rosales hanged herself at an open detention centre in Milton, Ont. In August, 2002 a sixteen-year-old girl hanged herself in a police holding cell in Moose Jaw, Sask. In October, 2002, sixteen-year-old David Meffe hanged himself in his cell at the Toronto Youth Assessment Centre. In the past year, two more young people have died while in custody in Ontario: A young person in open custody died after jumping from a facility van while it was moving in traffic, and another young person hanged himself at the Sprucedale Youth Centre.

This is not a complete list of deaths of young people in custody in Canada in recent years. No such list exists, making it difficult to track mortality trends in the youth justice system. This partial list does, however, allow the tentative conclusion that suicide is the dominant cause of death in custody, and that it is a persistent, and possibly growing, problem.

This problem demands at least two responses. First, we must take steps to monitor the deaths of young people in custody, at the national level. We need to document every death in custody so that we can then identify trends and take appropriate action. Second, Canada is far behind in research and practice regarding suicide in custody. While organizations like the Howard League for Penal Reform in the United Kingdom have developed numerous innovative and humane approaches to helping suicidal people in custody—many of which have been implemented by British prison authorities—the Canadian authorities continues to focus on crude and degrading measures like video surveillance, secure isolation and "security clothing".

We must move the discourse forward, beyond out-dated approaches of control and confinement, to one that is premised upon the dignity and autonomy of young people in custody. A national study or commission on suicide in custody—one that includes representatives from government and the mental health professions, but is driven by young people and child rights advocates—would be a good start.

Custody Rates and Closing Facilities

Across Canada, custody facilities are closing. In British Columbia, four youth custody facilities have closed in the past two years, the most recent being the High Valley Youth Correctional Facility. In Nova Scotia the Shelburne open custody centre was recently closed, making the Nova Scotia Youth Centre in Waterville the province's only youth facility. Recent high-profile closures in Ontario include the Toronto Youth Assessment Centre (scheduled to close by June 30), and Project Turnaround, the province's privately operated boot camp. The list goes on.

Some closures are making way for more modern facilities, but most are a response to a marked decline in the number of young people in custody. This decline in custody numbers suggests that the YCJA's promise of reducing reliance on custody is being fulfilled. At the same time, however, there are some reasons to remain vigilant.

Centralization of Facilities. As young offender custody populations decline, it is possible that provinces will look for ways to manage that population more efficiently. Large centralized facilities may be proposed as a solution. This approach should be discouraged for several reasons. First, centralized facilities move young people away from their communities, families and natural advocates, all of which are important supports during reintegration. Second, far-removed, centralized facilities are often not accessible to low-income families, thus discouraging family contact during incarceration. Third, larger facilities may be more susceptible to an institutional culture of control, disrespect and violence.

In the recent David Meffe inquest, the Youth Justice Action Group recommended that "new detention facilities … should be small, located within the community that they serve, and be easily accessible to family and community volunteers." The Youth Justice Action Group also recommended that open detention should be emphasized. These recommendations echo rule 30 of the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty. It will be important to monitor governments' plans for the custody and detention system in the coming months and years, and to advocate for the small, community-based facilities that will best serve young people in custody.

Replacement of Custody. It is also possible that some provinces will use empty custody facilities to provide an alternate residential service. Jails may be transformed into residential mental health or child welfare facilities. This has already happened at least twice since the YCJA came into force, in Nunavut and Prince Edward Island. In the case of Numavut, it was suggested in news reports that a recently closed custody facility may be used to provide residential services for troubled youth, including those on probation. In Prince Edward Island, a former custody facility was re-opened as a treatment centre for young people in child welfare care.

This practice is problematic because it undermines the Youth Justice Renewal Initiative's strategy to reduce the use of custody. A young person who is placed in a facility that is jail in every way except for its name is effectively incarcerated. Effectively incarcerating a young person through the child welfare or mental health system circumvents the numerous safeguards that exist in the youth justice system: Indefinite treatment might replace fixed sentences, and administrative discretion might replace court hearings.

Incarceration is particularly problematic when it is implemented through the probation system. If the crown intended to deprive a young person of his liberty, then it should have pursued a custody sentence in court. If the crown sought a custody sentence but failed, then it should respect the court's decision. In either case, when the government uses probation as a back door to incarceration it acts in contempt of our criminal justice system, and erodes the basic procedural safeguard that are intended to protect the rights of young people.

Although the decline in Canada's youth custody population is promising, we continue to face the risk that custody will not be eliminated, but will instead be displaced by another equally intrusive form of institutional care. Although it is important to advocate for the closure of custody facilities, we must not stop there. We must ensure that custody is not replaced by an equivalent form of institutional care, particularly one that entails fewer rights and safeguards than those in the youth justice system.

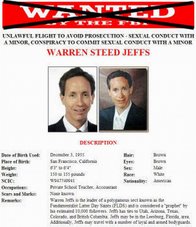

Presumptive Offences

One of the most troubling features of the YCJA is the "presumptive offence"—an offence for which a young person will be sentenced as an adult unless he can show that a youth sentence would be sufficient to hold him accountable. The law defines a presumptive offence as first or second degree murder; attempted murder; manslaughter; aggravated sexual assault; or a serious violent offence, if the young person has been found guilty of at least two previous serious violent offences. The presumption of an adult sentence applies if a young person is at least 14 years old (although the provinces can set the age higher, up to 16). It is legal to publish the identity of a young person who receives an adult sentence, meaning that young people who are sentenced as adults lose their right to privacy.

The YCJA allows adult sentences to be given for a large number of offences. In most cases, an adult sentence could only be given if the prosecutor applied to the court and was able to show that only an adult sentence would be sufficient to hold the young person accountable for the offence. In other words, the burden is on the prosecutor to show why a young person should be treated as an adult. For presumptive offences, however, the burden is shifted to the youth: It's up to the young person to show that an adult sentence isn't necessary. This reverse onus is at the heart of criticism of presumptive offences. Many child rights advocates argue that presuming that children will be treated as adults—even for very serious offences—represents not only an abandonment of Canada's commitment to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, but also violates the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

One of the biggest opponents to the YCJA's presumptive offence provisions is the Quebec government, which referred the provisions to the courts to determine whether they violate the Charter. On March 31, 2003 the Quebec Court of Appeal ruled that the presumption of an adult sentence and loss of privacy for young people violates the Charter. This decision was a declaratory judgment , meaning that only it expressed the opinion of the judges and did not strike down the law. Soon after this decision the Minister of Justice announced that the Government of Canada would not appeal the Quebec Court of Appeal's ruling, and would instead amend the YCJA.

Since that announcement Canada has a new Prime Minister and Justice Minister. However, there is no reason at this point to believe that plans to amend the YCJA have changed. It is likely that a bill to amend the YCJA will be introduced in the fall or after the next election, whichever is sooner. We should be somewhat concerned about the new bill. The government has indicated that it wants to focus on the Quebec Court of Appeal decision only, and is not opening the door to debate all manner of amendments. However, the YJCA has many opponents in many quarters, and in particular it is likely that the get-tough contingent will use the bill as an opportunity to re-stage its challenge to the YCJA.

In the past, the government has often been left to fight get-tough reformers on its own. This has resulted in get-tough reformers gaining a disproportionate amount of media attention and influence. It will be very important for child rights advocates to voice our support for the amendments and the many other good features of the YCJA when the new bill is introduced

No comments:

Post a Comment