Nathalie Des Rosiers President, Law Commission of Canada

Remarks for a speech at the 2nd Annual National Summit on Institutional Liability for Sexual Assault and Abuse luncheon held February 15, 2001.

Remarks for a speech at the 2nd Annual National Summit on Institutional Liability for Sexual Assault and Abuse luncheon held February 15, 2001.

Thank you for inviting me to participate in this very important conference on a subject which society and the legal system are often ill-prepared to acknowledge or respond to, namely the impact of sexual or physical abuse of children. I was asked to ``make the case for compensating secondary victims". Indeed, it is interesting that one would have to "make the case" for such compensation. The first part of this address will attempt to explain why it is even necessary to make such a case - why the civil justice system is suspicious of these claims. I will then proceed to make the case, psychologically, economically, and politically for compensating secondary victims and conclude with the challenges of attempting to do so.

My remarks are obviously inspired by the work of the Law Commission of Canada on institutional abuse. Its report, Restoring Dignity: Responding to Child Abuse in Canadian Institutions was released last spring and was in response to a reference from the Minister of Justice.

Before I move to the substance of the Commission's recommendations, I will say a few words about the Law Commission of Canada and its work and perspective in order to put my remarks in context.

The Law Commission of Canada

The Law Commission of Canada is an independent federal agency whose mandate is to provide advice on, improvements to, and modernization and reform of the law of Canada. It has defined its mission as a commitment to engaging Canadians in the renewal of the law to ensure that it is relevant, responsive, effective, equally accessible to all, and just. In approaching its mandate, the Commission is guided by a number of important principles:

- that its work be open, inclusive and accessible to all Canadians;

- that it view the law and the legal system in a broad social and economic context;

- that it be responsive and accountable by working in partnership with a wide range of interested individuals and groups;

- that it be innovative in its research methods; and

- that it take into account the impact of the law on different individuals and groups in making its recommendations.

Research Topics

The Commission believes it must look first at social problems as they present themselves to Canadians, and not be limited by the traditional legal and jurisdictional boundaries. From an understanding of these "real world" problems, the Commission can then examine how the law, understood broadly, is hindering or could facilitate their resolution. Consequently, the Commission has developed a research agenda based on four complementary themes: personal, social, economic and governance relationships. These themes are not meant to categorize discrete issues. Most issues could be examined from any one of these four relational perspectives. Rather, the themes represent a different emphasis in approaching issues.

Research Methodology

To determine the specific issues it will examine, the Commission seeks the views of Canadians. Initially, it conducted a broad public consultation to develop its strategic agenda of research. It then established an Advisory Council -- 24 volunteer members from across Canada - who bring a rich variety of experience and perspectives to the advice they offer the Commission. The Advisory Council meets twice a year to provide strategic guidance to the five commissioners regarding the projects that the Commission is considering undertaking. Members of the Council serve as an important network for the Commission, connecting it to communities, regions and points of view to which it might not otherwise have regular access.

The Commission selects research topics that it believes are of fundamental concern to Canadians. It approaches all of its work with a view to ensuring that it is multidisciplinary, consultative and, where possible, includes partnership. The Commission seeks to ensure a multidisciplinary perspective in a number of ways. It directs research contract opportunities to a variety of academic disciplines, such as sociology, economics, and psychology, as well as to lawyers, notaries and legal scholars. It seeks partnerships with different policy research agencies, with community-based organizations and other groups whose expertise complements the work of the Commission.

The Reference on Institutional Child Abuse

In 1997, the Minister of Justice asked the Commission to study the ways in which government should respond to institutional child abuse. What should be done for survivors of sexual and physical abuse? The Commission approached its work on this reference with the same philosophy that it applies to all its other research. It attempted to understand the problem in its social context, and to measure the consequences and the impact of the different legal mechanisms on victims, their families and communities. In the case of survivors of residential schools, it also examined the impact of institutional abuse on Aboriginal nations.

The Commission hired several teams of researchers who looked at both the international models and the range of options tried in Canada. The research involved interviewing survivors, and consulting with a wide range of individuals and groups, religious organizations, the Aboriginal communities, lawyers, therapists and community groups.

The report and the video Just Children were released in March 2000. The report had this to say about the needs of families and communities:

There are many ways in which members of a survivor's family can be affected by institutional child abuse. Some parents, particularly those whose children had special needs, sent their children away to school willingly, believing it was in the child's best interests to do so. In many instances, these parents did not discover until years later that their children had been abused. Some Deaf children with hearing parents believed that their parents knew of the abuse that was taking place at school, but sent them back anyway. As a result, these children became alienated from their parents and blamed them for the abuse they suffered. Their parents, in turn, now feel guilty for having failed to protect their children. In some cases the families are able to reconcile, but not always.

For Aboriginal parents who may have felt they had no choice but to send their children to residential schools, the guilt may be compounded. Often, the parents themselves had been residential school students. Therefore, they knew what experiences might await their children. However, where no schooling was available locally, and where there was a threat of fine or imprisonment for failure to surrender their children, parents may not have been in a position to resist.

Children who were physically and sexually abused while away from home frequently brought the effects of that abuse back to their families. Some abused children became abusers themselves, directing their violent behaviour at parents, siblings, partners and even their own children. Family members may suffer without even being aware of the abuser's own previous abuse in residential institutions.

In addition to experiencing the effects of physical and sexual abuse, the families of Aboriginal survivors also suffered the alienation of children who lost their language and their cultural heritage at residential schools. For these reasons, survivors and their family members share many of the same needs. Spiritually, they would benefit from an acknowledgement of the consequences of abuse, and an apology. Counselling to better understand and cope with the behaviour of survivors and to deal with harms survivors may have caused them is also a key need felt by many family members. Finally, because they have lived first-hand the spill-over effects of abuse, members of survivors' families are especially attuned to the need to see preventive measures and public awareness campaigns put into effect.

Communities are also affected by child sexual abuse :

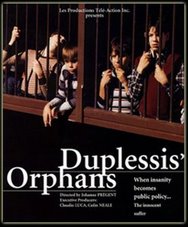

The damage caused by institutional child abuse, particularly abuse that has continued over a period of years or through more than one generation, extends beyond the individual survivors and their families: it affects entire communities. Communities are groups of people who live in a particular area or who identify with each other on the basis of common interests or common characteristics. In this sense, the idea of community would include, for example, a neighbourhood, an Inuit village, an Aboriginal nation, the Deaf community, or the community known as the "Children of Duplessis".

A community can be affected by institutional child abuse in profound and subtle ways, directly and indirectly. The difficulties experienced by the Deaf community, for instance, have been significant. They are exacerbated by the relative isolation of community members from resources, such as therapy, that are available in the hearing community. In a community where virtually all members have passed through the same institution, and many have been subjected to serious levels of abuse, in particular sexual abuse, it is hard to locate where an effective healing process might begin.

Small or tightly-knit communities are especially vulnerable to the ripple effects of institutional child abuse. They must integrate victims back into a community that may already contain victim-offenders. Even when the survivor's destructive behaviour is turned inward, communities will have to cope with the consequences. They must rebuild a sense of confidence in the community as a safe place for disclosure and healing. They must repair the rifts that have been caused by recriminations among community members where some survivors have themselves become perpetrators of abuse. They must replace (in the case of Aboriginal communities) or reform (in the case of the Deaf community) the institutions where the abuse took place, because the educational function performed by those institutions remains necessary and important. A population disproportionately prone to substance abuse and exhibiting suicidal tendencies puts enormous pressure on the healing resources of small, close-knit or isolated communities. Because many survivors simply do not have the education or life skills to become self-sufficient, this, in turn, places additional economic stress on the community.

Small or close-knit communities have needs much like those of families. Remembrance and acknowledgement of their on-going suffering is a first step to their empowerment. They may also need financial assistance to hire community workers and therapists to provide the support services and programs necessary to overcome the social and economic side effects of child abuse. These programs can also increase public awareness and promote prevention as a community goal.

On the subject of compensation for secondary victims, the report is therefore quite clear: any attempt to redress institutional abuse must look at the impact of the abuse on the victim's family, his or her community and, in the case of residential schools, on the Aboriginal nations to which he or she belongs. The Commission's report speaks to more than financial compensation however and this is an aspect which I want to emphasize. It is not only about money - neither for the primary victim nor for the family or the community. In addition to financial compensation, the list of survivor needs that emerged from the Commission's research includes acknowledgement, accountability, apology, access to therapy and education, memorializing and prevention.

The report, therefore, is about detailing how different legal mechanisms can respond to the various needs of victims and of their families and communities. It proposes changes to several mechanisms, the civil justice system among others, and encourages governments to move toward alternative dispute mechanisms that offer more flexibility than civil actions in attempting to respond to victims' needs.

I now move to make the case for compensation of secondary victims and want to start with a reflection on why it is even necessary to make such a case.

- Why the civil justice system is reluctant to compensate secondary victims

The unwillingness of the system to compensate secondary victims is rooted in part in its focus on individuality and a denial of the importance of relationships for human beings. The system's focus on individuality is pervasive. Casebooks tend to imagine and present one tort victim - who wants to be compensated as an individual. The story of the family or the community is rarely told. In fact, it is as a marginalized issue that compensation under provisions analogous to the Fatal Accidents Act is studied. It is only reluctantly that the system has accepted that the victim's family (defined by the Fatal Accidents Act or now the Family Law Act for Ontario) has a right to make a claim for damages. This focus on individuality is also demonstrated through the evolution of class actions: unless forced by legislation, the system would deny commonality and force people into arguing individual fault, harm and liability.

In short, the justice system does not like groups. It certainly does not like group litigation. It has therefore managed to focus most of its theories of compensation, or even of punishment and retribution, on individuals.

However, in reality, individuals are involved in relationships. They do not live in isolation and their connectedness to others is affected by harm of whatever nature. This recognition may be difficult to articulate in a civil justice system that values individuals first, and understands their wishes through the mechanism of legal representation. One lawyer per client: This mechanism of individual representation may be ill-suited to group representation, whether of families, or communities. I will come back to this issue later.

To the reluctance of the civil justice system to recognize groups and relationships, one must add its deep suspicion of psychological harm. A suspicion that is being challenged and conquered little by little by cases about abuse, but remains embedded in the system.

A third aspect of the reluctance of the system to be considered is the extreme concern about the possibility toward unlimited liability. As a civilian, I was always struck by the desire of the common law to establish categories for recovery. For a civilian, the idea of categorizing victims as primary and secondary does not inspire confidence. As you may know, the Civil Code states that if one causes damage to another, one has to pay... Hence, initially, the civil regime used causation as the way to curtail liability as opposed to attempting to define, in advance, the categories of people entitled to compensation. There has been some evolution in the civil law system as well and the distinction between primary and secondary victims which is now used, but there is little attempt to define the categories - spouses, children, and parents - in the civil law regime. It is simply a matter of proving that one has suffered damage, albeit indirectly.

The difference between secondary and primary victims is therefore rooted in the common law's fear of toward unlimited liability which seems to border on paranoia. I want to suggest that this fear does not sufficiently take into account the incredible financial and emotional barriers that exist to limit liability. The question to be asked is whether, in seeking to prevent unlimited liability, the system has not screened out too many meritorious claims. Striking the right balance is at the heart of our reflections on law and particularly at the heart of law reform efforts. We must always consider the impact of the invisible aspects of the system, and ask whether the absent players, the potential plaintiffs who do not even seek legal advice, should continue to be left out. This is one of the difficult questions for law reform in this area.

In light of these roots of scepticism in the civil justice system, it is incumbent on to reflect on the consequences of refusing to appreciate that people have networks of emotional support and live in relationships, which are affected by the harm caused by the tortfeasor. We must consider the case to be made for compensating secondary victims.

ll. The Case

The recognition that people, victims included, do not live alone and that the legal system cannot treat them in isolation is crucial to the work of the Commission, on this subject and on others. Limiting one's approach to responding only to needs of an individual means that you miss a large part of what the human condition is all about. Nobody is an island. In joy and in pain, human beings often join together.

I will try to make the case for compensation on three grounds, although there are many others. Let me explain why (I believe that) psychology, economics and even politics may support a case for compensation of families and communities.

- Psychology

"Je suis seul avec ma solitude" -- I am alone with my loneliness, sang Georges Moustaki in the 70s. Loneliness is the source of much anxiety and suffering. The importance of trust, of connections, of communication, or developing a sense of belonging and of connectedness to others is well documented in the psychological literature. This is what psychological health is all about.

Refusing to acknowledge this reality in the legal system seems to deny a fundamental need which comes with a cost -- a tremendous psychological cost. Suddenly, and lawyers representing survivors will recognize this, the plaintiff is alone in the face of the legal system. It is her case. Sometimes, this may be empowering for her. At times, it can distort the networks of support that she has created for herself. In one of the first articles on representing survivors of sexual abuse, Kimberley Crnich1 argued that survivors should be told that the lawsuit may break up their marriage, their families... This was the price to pay.

My question is whether this is a necessary price to pay. Psychological damage to individual claimants and their families and communities hurts us all. If the process of civil justice excludes or minimizes the role of networks of support, it loses the ability to adequately respond to the needs of litigants. The invisible family and community are left in the cold and denied the resources that our system can offer.

Further, think of the incredible psychological stress of the plaintiff who is awarded $500,000 only to become the target of her relatives who need money, of her family who is coping with the publicity and disruptions of the trial. Is it "her" money? Should she share it? Can she recognize their suffering? Should she have less because she does?

More and more, the psychological impact of the legal system on citizens is being studied. The American Therapeutic Jurisprudence movement is an interesting development in the literature that seeks to identify the psychological consequences of legal rules and concepts and of participating in the legal system. It posits that law should consider this psychological impact and seek to do ... less harm. Very radically, says the American Therapeutic Jurisprudence movement, people should not feel worse after their interaction with the law -- they should, if possible, feel better. It therefore invites us to ask the following questions on the subject at hand:

- How are families affected by the harm caused to one member?

- Does participation in the civil process allow for an expression of their trauma?

- Is such expression necessary to their healing? Is it better done elsewhere?

- Do family law claimants heal better than those who are excluded from participating?

We rarely ask these questions about our legal system, but it may be time to do so. It is no longer sufficient to rely on tradition or structural or procedural features of litigation to define the approach that law should have toward human suffering. Other disciplines may have something to offer. This brings me to the economic analysis of the question.

- Economics

Most Law and Economics scholars reflect on the impact of negligence and compensation schemes on the tortfeasor, the insurance industry, and explore the efficiencies of the system. One question that has not been explored very much, to our knowledge, whether it matters who receives the award.

Our consultations have certainly revealed that there is a great deal of disruption in a community when one member receives a large sum of money, sometimes arbitrarily. He is the survivor whose case was heard first, whose institutional file was not lost or whose lawyer was most diligent. The community needs the money and the successful plaintiff is asked for contributions. This form of redistribution of wealth is often done on an unprincipled basis - more is given to the loudest claimant. It is also done without much help to the successful plaintiff who may need the support of the community for his or her own healing. At times, this redistribution of wealth has led the successful plaintiff to become destitute.

Structured settlements were a response to the fear that plaintiffs would become destitute because of their inability to manage large sums of money and their weakness to the pressures of the market to "spend, spend, spend". Not unlike many of us, who appreciate deductions at source and mandatory pension contributions, some plaintiffs opt for structured settlements. Is compensation for the secondary victims another tool to protect the successful plaintiff from pressures - not market pressures but social pressures, to "give, give, give"?

Would it be more efficient to compensate the community directly instead of through the plaintiff? Certainly, some Aboriginal communities have taken the position that the harm caused by sexual abuse was collective as well as individual and that denying the collective nature of the harm is incoherent and wrong. It could also be very inefficient. It could very well be that a direct contribution to the community for the harm suffered would allow for better community healing. Our consultations brought to the forefront in the context of residential schools that healing outside the community setting was not always possible and diminishes the nature of the wrong. It is one of the reasons why the Law Commission suggested that more redress programs, which offer greater possibilities of community responses, be developed. Nevertheless, there is no reason why the civil justice system could not adapt and recognize this evolution of thinking. Class actions, collective rights, and now collective harm, present the justice system with the possibility and the challenge to improve and better respond to society's needs.

- Politics

It is rare that one argues that political developments could be helped by the justice system or that they could be a positive thing. Nevertheless, the argument presented here simply reflects one personal conclusion that I drew from my participation in the work of the Commission on institutional child abuse.

There often was a political context to institutional abuse. Our study certainly outlined that the children placed in institutions were often the poor and the marginalized - Aboriginal children, children with disabilities and economically disadvantaged children. The civil lawsuit is then a way to redress systemic failures or systemic injustices and also a way to raise the profile of the issue of abuse of children.

Disconnecting survivors from each other and from their family and community is disempowering. It is hard to see oneself as part of a "class" if the message from the system is that the harm is experienced solely as an individual.

What was also interesting is how survivors become powerful spokespersons on the issue of child abuse. This responded to their need for prevention. In that sense, they responded to the political needs of society which requires good advocates and ongoing monitoring of how society addresses the child abuse issue. Often, the recognition of connectedness to either a family or a community, is one way of identifying the breadth of the harm caused and of the "political" context of the abuse. It may allow for more engagement with the systemic nature of the needed response.

I do not want to overemphasize this point which is unusual, but I simply want to connect recognition of harm and political action because my observation was that most survivors insisted that one of their strongest needs was to see that measures were put in place to prevent harm to other children. Further, the ones who had benefited from a group experience -- the Grandview survivors, for example - had often risen to the challenge of acting as spokespersons on the issue of child abuse.

Certainly, one can make a similar observation for the Aboriginal communities that sought group solutions as well as individual compensation. The group reflection allowed them to move from the past to the future and to use their past abuse as a springboard for action so that it "never happens again".

What would be the consequences of considering compensation of secondary victims as an important and no longer a subordinate function of the civil justice system?

lll. The Consequences

I think that there is a good case to be made that compensation for secondary victims is an important function of the civil justice system. However, there is no magical solution in any area of legal development. On the positive side, one should note that courts are increasingly recognizing the pain and suffering of families. Many ADR processes do address the needs of families and even the needs of communities. This is not without problems. I allude to the problem of representation: Who is the client? Is it the family? The community? The survivor? Can we afford to provide everyone with legal representation?

Further, one has to recognize the diversity of healing strategies of survivors. Every time that one seems to approach a solution, for example, embracing alternative methods of redress, we find that there are survivors for whom this will not work. We just do not know how people heal from sexual abuse. The survivors are the experts. They are the only ones who really know what they need and they are the ones who are developing the knowledge as they struggle through the healing process.

Some survivors will argue no doubt that their families and communities ought not to be part of their own suffering. Their definition of harm does not include their families: They want redress to be personal and individual. That is the way in which they understand their healing. Painfully alone. That is a concern: The primary victim may not want his or her family involved in the lawsuit, and may not want this additional burden of hearing them testify as to why she was a bad mother, how he was a bad son, etc.

Ultimately, and this was the final conclusion of the Law Commission's report, choice is necessary. Survivors must have some choice in terms of their approach to redress because no one process meets all their needs. Survivors should also have the choice of whether to include their families in their civil process of recovery. Other avenues can be offered to families and communities. No one process, no one lawsuit is enough to fully respond to the complexities of human suffering. We must provide choice and continue to reflect on the best ways of including all those who should have a voice in the legal system.

The challenges are great and we do not have much choice: The law is there for the citizens and not for the system. It must respond to the evolving needs of its citizenry. I hope to have provided you with food for thought following this wonderful lunch and I thank you for your attention.

__________________1 Kimberly A. Crnich, « Redressing the Undressing: A Primer on the Representation of Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse » (1992) 14 Women's rights Law Reporter 65.

No comments:

Post a Comment