'Modern science has it well in hand':

Nova Scotia's 'experiment' in eugenics

By STEPHEN ELLIS*

30 April 2004

Canadian Legal History

Dalhousie University

"Behold ye simple moron,

He does not give a damn,

I'd hate to be a moron,

Ye Gods! Perhaps I am."

The Medical Society of Nova Scotia [1]]

HALIFAX, NS -- IT WAS sixteen years before those fateful days in May, 1945 when the consequences of the German eugenics movement and the Nazi program of Josef Mengele could no loner be denied.

On the occasion of the founding of the Brookside Training School in Nova Scotia, Dr. Samuel H. Prince [2], noted social reformer and mental hygiene society president, exemplified the tireless commitment of many of his generation of progressive activists. Progressives of this period agitated for a better world, one where science, humanism and Christian values would play a large part. There were many evils to be overcome in the early part of the twentieth century, tuberculosis, influenza, among others, and more and more, people were putting their faith in science as a way to cure society's ills.

For middle-class progressives, however, no phenomenon matched in gravity the type of danger the existence of "feeble-minded" people represented in Nova Scotia. And on this November day in 1929, the campaign against the blight of "feeblemindedness" had for the most part reached a successful conclusion: a publicly-funded institution had been established to ensure this "most pernicious element" was eliminated from the arteries of the nation. [3]

The Brookside Training School, one of the earliest of its kind (along with Shernfold, Orillia and Red Deer [4]), represented the high-water mark for eugenics-inspired social policy in Nova Scotia. Going back as far as 1895, the Halifax Council of Women with Mrs. J.C. Mackintosh at the helm was agitating in favour of such a measure. [5] In 1987, Dr. W.H. Hattie headed a special committee of the Medical Society of Nova Scotia to push for the segregation of the feeble-minded. [6] As Dr. Prince remarked in a speech on the occasion of the school's opening in 1929, "Such institutions are recognized as of prime importance to every nation for feeble-mindedness uncontrolled, will sap the roots of civilization itself." [7] The menace that "gravely" threatened the "social, moral and economic welfare of the province" [8] had been contained.

Boiled down, eugenics is the notion that the quality of the human race can be improved through selective breeding. It is based on the assumption that individual traits are passed through heredity. Francis Galton first popularised this form of determinism in 1865:

If a twentieth part of the costs and pains were spent in measures for the improvement of the human race that is spent on the improvement of the breed of horses and cattle, what a galaxy of genius might we not create! We might introduce prophets and high priests of civilization into the world as surely as we can propagate idiots by mating cretins. Men and women of the present day are, to those we might hope to bring into existence, what the pariah dogs of the streets of an Eastern town are to our own highly-bred varieties. [9]

Gregor Mendel's pioneering work in the field of heredity was seen as further proof of the determinative nature of our genetic make-up. According to Callinicos:

Eugenics ... asserted (1) that social structures are caused by, and therefore must be explained in terms of, biological structures, and (2) that "race", conceived as a set of fixed characteristics transmitted by inheritance, is the most important of the biological structures on which social structures are based. The obvious implication was that the main way to improve society was to encourage the racially èsuperior' to mate with each other, and to discourage èinferior' types from breeding at all. [10]

For many who were persuaded by the ideas of eugenics there was no greater threat than the "feeble-minded" person. The term "feeble-minded", however, lacked a precise clinical meaning and functioned as a catch-all for those who would find themselves on the margins of society; the mentally challenged, the underachiever, the runaway, the unwed mother, children from broken homes. All fell into this class of people whose very existence undermined the harmony of society. [11]

In particular, the term became popularized through the work of Dr. Henry Goddard of Vineland, New Jersey. His study related the story of one Martin Kallikak who married an attractive, but "feeble-minded" woman, and the long line of "defective" unions that resulted. The doctrine held that the "germ plasm" of mental defect was passed on from parent to child through the iron laws of heredity. [12]

Maude Merrill in a 1922 article in the Dalhousie Review reflected well the tenor of the time:

The Nams, the Kallikaks, the Zeros and the rest of the innumerable tribes of Ishmaelites, unearthed in our insatiable thirst for the truth about heredity, have abundantly proved that certain mental traits are characteristic of generation after generation of the same stock. [13] ... The social significance of inferior mental capacity is strikingly apparent in its intimate relation to all forms of anti-social conduct. [14]

Alexander P. Reid, Dean of the Dalhousie Faculty of Medicine from 1868 to 1875 and Superintendent of the Nova Scotia Hospital for the Insane, was typical in many respects of the middle-class professionals of his time. His faith in eugenics was unwavering:

Eugenics steps forward as the guide that can safely pilot it [society] to the safe harbours of health, wealth and desirable possibilities ... and points out the means by which the undesirable recession in race propagation can be controlled, nay, eliminated. [15]

F.C.S. Schiller, humanist philosopher and founder of the English Eugenics Society, laid out the basics of the eugenic doctrine in an essay for the Dalhousie Review:

The license society allows at present to the criminal, the insane and the feeble-minded to multiply at pleasure, and to have their worse than worthless offspring cared for at the public expense, or rather, at the expense of those who feel too heavily taxed to produce children that would yield better returns to the community [16] ... The gist may be stated in a single sentence. Society, as at present organized, wastes its good material and extirpates its better stocks, while it recruits itself from its inferior elements. It does this unconsciously and unintentionally, but at a growing rate. [17]

As faith in nineteenth-century liberalism declined, social Darwinist ideas guaranteeing "survival of the fittest' ensured that eugenics was planted in very fertile soil. The belief in the right to be "well-born" had literally swept the world. In the United States sterilization laws were enacted in as many as thirty-one states and became the inspiration of the later Nazi eugenic campaign in Germany.

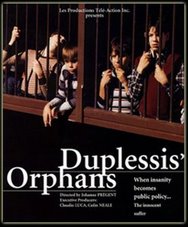

Canada, too, took up arms against the foe from within. Alberta's sterilization laws remained on the books until 1972.18 In its forty-four years, Alberta's Sexual Sterilization Act had authorized four thousand, seven hundred and twenty-eight sterilizations, and was directed disproportionately at women, and people of aboriginal and Eastern European descent. [19]

Shockingly, it has been noted that as late as 1978, hundreds of sterilizations were being carried out annually in the province of Ontario.20 Doctors were telling women seeking therapeutic abortions they had to submit to sterilization as part of a "package deal". [21]

Contrary to popular belief, the tenets of eugenics in turn-of-the-century Canada were almost universally accepted and this was no less so in the province of Nova Scotia.

Yet, Nova Scotia has escaped making the short list of provinces that experimented in eugenics. For most familiar with the subject, Alberta's 1928 Sexual Sterilization Act and British Columbia's five years later were the height of government intervention to stave off racial degeneration. [22] But Nova Scotia also gave eugenic or mental hygiene ideas a legislative form. After two Royal Commissions (in 1916 [23] and again in 1926 [24]), Bills 174, 84, 70 and 64 were passed into law in 1927.

The same urgent concern that had preoccupied proponents of mental hygiene in other parts of North America could be seen with equal intensity in Nova Scotia. Although Nova Scotia preferred the eugenic measure of segregation rather than sterilization, the "unfit" would not be permitted to reproduce their kind [25] lest society be submerged in a flood of congenital feeblemindedness. [26]

Eugenics as social policy: Canada

History has now provided ample evidence that eugenics was far from a passing fancy in Canada. Some of this country's most prominent social reformers were quite naturally believers in the need for eugenic measures to protect the nation against racial degeneration. People like J.S. Woodsworth, Tommy Douglas, Charlene Whitton, Emily Murphy, Nellie McClung and Agnes McPhail, among many others attest to the fact that far from being the preserve of a fringe group, eugenic ideas were mainstream. [27]

The medical profession in particular took an early interest in the need to combat "race suicide" in Canada. In a piece read before the American Medico-Psychological Association in 1900, Dr. James Russell of the Hamilton Asylum opined that while there were many processes that aimed to "destroy the moral and intellectual fibre of the race," [28] the elevated status of the Anglo-Saxon race would not be undermined. Speaking in less than subtle metaphors, Dr. Russell painted the picture thus:

The immense virility of the Anglo-Saxon race, like that sturdy oak, may resist the encroachments of the canker worm for generations, but unless purge and purified of the disease it will at last crumble and decay. [29]

No individual was more prominent in the campaign against "mental defectives" than public health crusader Dr. Helen MacMurchy. Next to successful campaigns on such vital issues as birth control and infant mortality, MacMurchy saw dealing with the problem of the "feeble-minded" as a national priority. With a rather disconcerting mix of compassion and cold-heartedness, MacMurchy in her 1920 book The Almosts: A Study of the Feeble-Minded viewed the problem in this way:

It is the age of true democracy that will not only give every one justice, but will redeem the wastes products of humanity and give the mental defective all the chance he needs to develop his gifts and all the protection he needs to keep away from him evils and temptations that he never will be grown up enough to resist, and that society cannot afford to let him fall victim to. [30]

Dr. MacMurchy was a fervent advocate of the forcible segregation and sterilization of mental defectives and claimed that society would pay dearly in "expense, crime, immorality, crime and national degeneration" if these "unfortunates" were allowed to reproduce. [31]

Mentally defective children become mentally-defective men and women -- mentally defective paupers and criminals ... then the community must be protected from the feeble-minded and the feeble-minded must be protected from many in the community who would lead them into evil ways. [32]

[Otherwise] we are wronging them if we go on allowing them to become parents, as we have done in the past in Ontario, wronging their miserable children who should never have been born, and wronging our country and the community by entailing on them that heavy burden of expense, and that heavier burden of crime, vice, misery, and degeneracy which mental defectives always cause. [33]

More than a few sources, MacMurchy among them, pay tribute to the early work of the National Council of Women (NCW) in bringing the "menace" of feeble-mindedness to the attention of the Canadian public. Importantly, Angus McLaren in his work Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada 1885-1945 points out that the National Council of Women was the first organized group to take up the campaign for segregation of the feeble-minded. [34]

In a National Council of Women pamphlet entitled "Lovest Thou Thy Land?" located in a scrapbook of the Halifax Council of Women the particular urgency posed by the Great War had posed the question in stark terms.

Thousands of Canada's best are being slaughtered on European battlefields. Our duty to our country demands conservation of the life at home. The feeble-minded in our midst are therefore a greater menace than ever. We have learned certain facts regarding the problem of the feeble-minded, but we need to know much more ... This European war is a monstrous sort of selection of the unfittest for the ruin of the species. [35]

In a similar vein, a Toronto Department of Public Health bulletin released in 1916 warns against the dangers of letting mental defectives breed out of control. Taking a cue from the breeding of plants and animals, Dr. Hastings asks:

What safeguards are being used to secure only the reproduction of the fit in the human stock? What precautions are we taking to prevent the reproduction of the mentally defective? Absolutely none. If the farmer who breeds from his most inferior and worthless stock, as well as his best, is classed may we expect to be placed who are making no effort to prevent the reproduction of the feeble-minded, who in addition to being a burden on the State, have an appallingly demoralizing and degenerating influence on the whole race? [36]

Again, the carnage of the First World War killing off the "most fit" among us was more than a little cause for concern:

Many of the best of our stock are being sacrificed and will be sacrificed. Can we afford, in the nation's interest, to add insult to injury, by permitting the defective class to be constantly reproducing themselves? The only way to reduce the number of the feeble-minded is to make impossible their reproduction, and to make impossible their entry into the country. [37]

The Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (CNCMH) was formed in 1918 by Dr. Clarence Hincks and Dr. Charles K. Clarke and took upon itself the task of advising governments about how to identify and eliminate the problem of feeble-mindedness through testing, segregation and sterilization. Hincks and Clarke promoted themselves as experts on the subject of feeble-mindedness and offered their services accordingly. For decades, the CNCMH functioned as Canada's most effective eugenics lobby group and could count among its listed Halifax members Dr. William H. Hattie, Dr. Eliza Brison, Dr. F.E. Lawlor, Lieutenant-Governor Grant and one-time premier of Nova Scotia, the Hon. Ernest H. Armstrong. [38]

The CNCMH bulletin called for governments to take immediate steps for the "care" and "protection" of mental defectives in the better interests of society. The February 1920 issue of the Mental Hygiene Bulletin, also found among the Halifax Council of Women papers, made the then rather uncontroversial statement, "The magnitude of the evil thus left untouched is very great. There is no more potent influence in the production of vice and crime than the unwatched mental defective. [39]

In the same bulletin is a 1919 report by the Hon. Justice Frank E. Hodgins who chaired the Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-minded in Ontario. The importance of "prevention" was the highlight of his presentation:

If the cardinal fact could be assimilated that the elimination of the mental defective from the school and from the street and from the agencies engaged in reforming character would render the efforts of teachers and social workers comparatively easy and empty the jails of over half their inmates, and that these unfortunates can, if taken in time, be made comparatively happy and useful, there would be little time lost in bringing about the desired result. [40]

On page fourteen of the bulletin, just below the announcement of a planned CNCMH survey of mental defectives in New Brunswick is a revealing Grimm-like story called "Children versus Foxes". Drawing an explicit parallel between human and animal breeding, the story recounts the experience of an out-of-town visitor who happens upon a particularly wise fox farmer:

A conversation with the caretaker revealed the fact that he was a keen student of Mental Hygiene, and at his own suggestion took the visitor to a wired enclosure in which there was a mentally deficient fox. When questioned as to whether he intended using this specimen for breeding purposes he held up his hand in protest and said that if he followed such a policy his industry would be ruined. [41]

The idea that radical measures were required to stave off racial degeneration was common ground among progressives of that era. When speaking of mental hygiene measures in 1915, Dr. Helen MacMurchy spoke of its tenets being "universally accepted". [42]

The mental hygiene movement in Nova Scotia

The politics of eugenics (or mental hygiene, as it become known) had equally erstwhile proponents in the province of Nova Scotia. As early as 1890, Alexander P. Reid in a paper read before the Nova Scotia Institute of Natural Science, viewed the danger the feeble-minded posed in alarmist terms: These "ulcerous and diseased outgrowths on society" whose affliction is "sixty to eighty per cent" inherited will pass away with sufficient effort. [43] Speaking of the "tyranny of defective organization," Dr. Reid remarked, "There are many congenital defects, but crime, idiocy and insanity are the most potent for ill in the culture of the race, and will society not interfere to protect its successors when they cannot help themselves?" [44]

In an article written in 1913 entitled "Eugenics", Reid speaks in terms eerily reminiscent of the later Nazi campaign against the Jews:

[M]ust society continue to be oppressed by this increasing mass of expensive and worthless humanity ... Were these ideas carried out the whole lot of irresponsibles, imbeciles and criminals would be eliminated in two generations, and some States are now on the high road for this termination ... if we cannot reach perfection let us get as near as we can. [45]

Loyal to the idea, Reid reiterated that the source of the "problem" must dealt with conclusively: "The disciple of Eugenics is thus given a sound basis upon which to construct practical work and formulate laws which can in time eliminate the undesirable elements of society." [46] Lamenting the fact that the Nova Scotian public remained unfavourable to the recourse of sterilization, Reid settled for segregation: "Let us place all the feeble-minded under such restraint that procreation be prevented." [47]

Probably the most active member of the medical community in Nova Scotia to take on the "problem" of the feeble-minded was Dr. W.H. Hattie, Medical Superintendent from 1898 to 1914 and Provincial Health Officer from 1914 to 1922. In an article called "The Prevention of Insanity", Dr. Hattie's analysis mirrors that of others engaged in this battle: "The average imbecile is not of much use as a citizen. He is usually at least in some degree extra-social if not anti-social. But he is capable of procreating his kind." [48] State intervention, according to Hattie, was also necessary to ensure couples were "properly" paired. With respect to the feeble-minded:

More than mere suasion is necessary to any measure of success, however, and there is good sense in the efforts which some lawmakers are putting forth to prevent promiscuous marrying and to place some restrictions on the marriage of the unfit. [49]

Seven years later in an article of the same title, Hattie developed on his idea of the type of "suasion" necessary. In the event the deemed defective demonstrated any sexual impulse, the state must intervene:

When there is evident defect, particularly if any tendency to eroticism is manifest, the safety of the community, as well as of the unfortunate individual, demands segregation in a suitable institution. This costs more than sterilization or the lethal chamber, but does less violence to sentiment. Some authorities, as Archibald R. Douglas, of the Royal Albert Institution, assert that the imbecile is a much more potent agent in producing racial deterioration than the lunatic. I doubt if we have any more pressing need in Canada today than the proper provision for the feeble-minded members of our country, particularly those who are still sexually competent. [50]

In an article entitled "The Physician's Part in Preventing Mental Disorder", Dr. Hattie repeated the mantra of the mental hygiene movement:

The so-called lesser grades of mental defect are perhaps really those of paramount importance, for these are accountable for a very large share of the criminality and immortality and delinquency and pauperism which cost us so dearly, and it is these lesser defects which are most likely to be passed on from generation to generation. The problem then is many-sided, and bears so intimately upon national efficiency and national progress that we cannot afford to disregard it. [51]

Echoing the apocalyptic tone of his contemporaries across the continent, Hattie warns of a national emergency; only the fittest will survive on the national and international stage:

Canada is faced today with a situation not less perilous that that involved in accepting the challenge of the Hun. We have entered upon a period of competition such as never before dreamed of. Our place among the nations depends upon our ability to meet this competition, and this in turn depends upon the physical, mental and moral qualities of our people. [52]

Hattie's eugenics was also heavily laced with a virulent social Darwinism:

The struggle for existence can best be endured by those who are fittest, while those of limited endowment may be practically compelled to resort to questionable means of acquiring the necessities of life ... This will go far not only towards assuring our people the comfortable enjoyment of life and preparing them for success in the competition with other peoples. [53]

The consequences of not taking these "unfortunates" "in hand" are equally dire. With the usual combination of care and callousness so typical of the movement, Dr. Hattie adds, "It is a mercy to protect him [the mental defective] from the world; it is a folly not to protect the world from him." [54]

I. A movement is born - The Halifax Local Council of Women

In one of the very few references to Nova Scotia, McLaren in his work points out that Canada's first eugenical movement was formed in 1908 in Nova Scotia in the form of the League for the Protection of the Feeble-Minded. [55] True as this may be, organized agitation in support of eugenic measures in Nova Scotia was taken on by the Halifax Council of Women (HCW) at least a full decade earlier. And given the boundless energy and influence of such women as Mrs. J.C. Mackintosh, Mrs. Charles Archibald, and later, Mrs. Agnes Dennis, the dubious honour rightly goes to the HCW.

Dr. Prince's speech on the opening of the Brookside Training School gives us a thumbnail sketch of the birth of a movement. As early as 1895, he credits the HCW, "the honour, in an organized way, [of] calling attention to the appalling conditions related to mental deficiency in the province and in advocating governmental rather than private institutions in coping with the problem." [56] Dr. MacMurchy also related that in 1897, at an annual meeting of the National Council of Women held in Halifax, a Dr. Rosebrugh addressed a letter on the subject of the problem of the feeble-minded. [57] And possibly as

early as 1906 Mrs. Agnes Dennis and HCW had begun to organize their own survey of the province, sending a circular to doctors, clergyman, overseers of the houses, refuges, etc., in the province of Nova Scotia with a view to finding out the names, ages and conditions of such persons." [58] And according to Prince, as many as a thousand questionnaires were sent out, the expense of printing and mailing absorbed by the provincial government. [59] Apart from the vital issues of extending the franchise to women and whether or not women should serve on school boards, the problem of eliminating the scourge feeble-mindedness was priority number one for the HCW.

A series of letters and regular columns in local newspapers do much to shed light on the sense of urgency felt by Council members. The problems of crime, immorality, vice, pauperism, illegitimacy, drunkenness, and venereal disease were all linked to a phenomenon that many felt was breeding out of control. There was absolutely no question that mental defectives represented, as Jane Wisdom reported in The Echo, "the root of all social evil". [60]

Criminality was rooted in the genetic makeup of the mental defective who roamed loose, waiting to strike. On Saturday, March 7, 1908, Miss Wallace of the HCW wrote to The Mail:

In a word, they compose a class difficult to define, but not difficult to recognize ... Probably the reason they belong to the criminal class is that they are feeble-minded. What can be done for them? ... Now is the time to take hold of these mentally defective children, and make something of them, that they may not become degenerate unemployed criminalsóand perhaps, alas, the parents of children still more mentally defective, degraded and dangerous to the community at large. [61]

Mrs. Sexton of the International Order of Daughters of the Empire (I.O.D.E.) confidently made the following comparison:

Statistics carefully gathered in the United States and the foremost countries of Europe show the fact that for every fifty normal inhabitants of a country, there is one feeble-minded person. This is, of course, an approximation, but roughly, it would indicate that here in Nova Scotia there are nearly one thousand mentally defective or feeble-minded persons ... They are walking our streets, a constant menace to our community safety. [62]

Mrs. Stead and the Press Committee of the HCW add their voices to the virtual certainty of the hereditary transmission of mental defect:

We are now burdened with an ever increasing burden of providing for incompetents; for these are almost certainly hereditary, and the progeny of the feeble-minded woman is often cursed with the awful legacy of vice on the one side, mental and moral defects on the other. [63]

Then it must be remembered that feeble-mindedness is hereditary in more or less of its symptoms. For instance, feeble-mindedness begets drunkenness and immorality and alcoholism in their turn beget feeble-mindedness in a continuous vicious cycle. [64]

The inverted logic of eugenics is seen in a letter written by "An Old Print" to The Mail:

The question today is not so much "what shall we do for the feeble-minded prostitutes," but should be "What shall we do about the cause that produced prostitutes." ... If you set out to clarify a filthy steam, you first find the source that made it filthy, and remove the cause. [65]

Part of the eugenic narrative is the belief that feeble-minded mothers are afflicted with an "unusual fecundity" [66] and are therefore responsible for the large number of "illegitimate", feeble-minded children born into society. "G.T." of the HCW recounted the popular story of "The Jukes" in her letter to The Recorder:

Dr. McCulloch, in his book, "The Tribe of Ishmael," studies the descendents of one diseased man, John Ishmael, and, in a period of forty-eight years, traces five thousand degenerates who have committed almost every known crime. Richard Douglas compiled the history of another family, "The Jukes," the descendents of five degenerate sisters, in which he traced the careers of twelve hundred persons, one repeated tale of disease, insanity, idiocy, and crime. What enormous expense these two families alone have been to their country!" [67]

Mrs. Agnes Dennis of the HCW related a local example of this worrisome phenomenon:

Some years ago the Women's Council asked the Superintendent of the Halifax Poor House for the number of children born of feeble-minded mothers in that institution in five years. The answer was twenty. These twenty children were the offspring of nine feeble-minded mothers. One had born one child, five had born two and three had born three each. This deplorable report can probably be duplicated by the superintendents of most of our provincial poor houses or poor farms. [68]

The minutes taken at the 1920 annual meeting of the HCW are also of interest. The urgency of this vital mission is difficult to overlook:

There is nothing vague about it. Modern science has it well in hand. Feeble-mindedness is a failure to develop. It is a danger to the community. He [Dr. Fraser-Harris] instanced their mania for fire, carelessness with fire and weapons, tendency to crimes in sex and prostitution. They are often physically degenerate, often become criminals. The juvenal courts often have to deal with them ... Eugenics aim to have parental conditions right; to be well born is not a matter of heraldry, but of physiology." [69]

II. The Nova Scotia League for the Protection of the Feeble-Minded

The group with the well-meaning name was formed on June 3, 1908, no doubt at the inspired instigation of the HCW. [70] The League for the Protection of the Feeble-Minded, with the Lieutenant-Governor of the province, J.C. Tory, as its honourary president brought together people from many walks of life to carry out this vital social task. Dr. William H. Hattie, Ernest H. Blois, Sir Frederick Fraser, Judge Wallace, Archbishop McCarthy, Agnes Dennis, Eliza Ritchie, Mrs. F.H. Sexton of the I.O.D.E., and Dr. Frank Woodbury. Later, as the Nova Scotia Society for Mental Hygiene, it would involve such personalities as A.H. MacKay, Superintendent of Education, and Dr. Samuel H. Prince, founder of the Maritime School of Social Work, Kings College professor and prominent social reformer.

From very early on in its life the League had easy access to power in the province. The League's minutes for March 9, 1909, demonstrate the willingness shown by then Premier George Murray to accommodate the ambitious plans of the League:

Dr. Fraser [later, Sir Frederick Fraser -- S.E.] then urged on the government the necessity of starting immediately to deal with the matter in a practical way. Especially the part of the work which concerns feeble-minded children ... The premier showed great willingness to do anything in his power to help this work of the league. The government promptly agreed to have printed and circulated free of charge all literature prepared for the purpose of the league; to use existing government officials throughout the province to collect definite information concerning all feeble-minded persons in the province and to appoint A.S. Barnstead, Dr. A.H. MacKay and Dr. W.H. Hattie to act with and assist the committee in the campaign of education which is about to be started and in the collection of information and formulation of a definite plan for the protection of the feeble-minded to be submitted to the government on a later date. The premier suggested that something might possibly be done very soon as a piece of land near Dartmouth recently acquired by the government ... It was decided to make an attempt to secure the support and cooperation of influential religious and secular bodies. [71]

For years, activists has focused on the need for an institution as the most effective way to segregate, or as the League put it, "care" and "protect" the feeble-minded. The entry for November 9, 1909, read as follows:

The committee [Dr. Fraser, Mrs. Agnes Dennis, Dr. Eliza Ritchie, Dr. E MacKay and the secretary] agreed that for the present the institute must be either a provincial government or a private corporation receiving government support in some form ... It was moved and seconded that a committee be appointed to interview the government for the purpose of having an investigation of the number, conditions, needs and causation of the feeble-minded of the province. [72]

The modus operandi of the League was agitation. Public meetings, recruitment and pressure on public officials were the ways it could count its success. By 1912 the League could boast fifty branches throughout the province. [73] A.H. MacKay, E.H. Blois and W.H. Hattie were the League's devoted leadership and, not surprisingly, they were the chairmen of the provincial government's "Report Respecting Feeble-Minded In Nova Scotia" in 1916.

III. The Murray and Rhodes governments respond

On two separate occasions, in 1916 and again in 1926, the Nova Scotia Legislature saw fit to organize royal commissions to investigate the nature of the social danger facing Nova Scotians. Interestingly, both inquiries found that the social, moral and economic welfare of the province was "gravely menaced" and that immediate steps had to be taken to "limit the multiplication of this unfortunate class". Moreover, both commissions concluded that sterilization as a method of selective breeding, though effective, offended popular sentiment. [74] Instead, the more "cost effective" method of segregation was preferred; "defective" boys would be required to learn a trade so as to become a productive member of society and "defective" girls would be kept in care until the child-bearing years have passed. [75]

Both inquires drew the same conclusions about the societal impact on the "unwatched" mental defect:

We may reasonably assume that this condition is responsible for a very considerable share of the pauperism, illegitimacy, vice, and crime which exist in our province, and we are aware that the defect is one which is singularly prone to be transmitted from parent to child. It would, therefore, seem reasonable that from the economic, as well as from the moral and sociological points of view, a strong effort should be made to limit the multiplication of this unfortunate class. [76]

The survey staff found that mental defectives in the province were contributing, out of all proportion to their numbers, to such social problems as dependency, pauperism, spread of disease, delinquency, immorality, illegitimacy and prostitution [77] ... The present cost of mental deficiency to the province exceeds three hundred and fifty thousand dollars per annum." [78]

It is obvious that unless methods are developed in Nova Scotia to prevent the feeble-minded from having children, the mentally deficient will increase by leaps and bounds. [79]

The 1926 report appears to be the more reliable of the two in terms of methodology. It had called many witnesses from the Nova Scotian community and hired an outside organization to carry out a survey of mental defectives in the province. The 1916 report, on the other hand, looks to be a record of the personal opinions of its chairmen, namely E. H. Blois, A. H. MacKay and W.H. Hattie.

But the differences between these two efforts are more apparent than real. While both seem to follow radically different methodologies, it is remarkable that both arrive at the same conclusions and make identical recommendations. It is difficult to account for the fact that two different approaches, one insular and polemical, the other broad and inclusive, arrive at identical positions. Unless, of course, one takes a glance at the quality of the evidence brought before each.

The 1916 inquiry quite literally had no evidence to support its wide-reaching conclusions and recommendations. Whenever the chairmen introduced evidence to support its premises, they were largely from dubious American sources, relying unabashedly on an empirical "double inference". One was first asked to believe that American evidence supported the premise that the "unfit" threatened the fabric of American society. Then, one is asked to infer yet again, that since this phenomenon existed in the U.S., then it must also exist in Nova Scotia. The appalling paucity of evidence, however, did not seem to deter its zealous chairmen from recommending some rather far-reaching societal changes.

By contrast, the 1926 inquiry had undertaken a consultative and empirical process that had cloaked it in an unquestionable legitimacy. Numerous "persons of undoubted integrity" had presented briefs before the committee. What is more, a province-wide survey of "mental defectives" was carried out by a very reputable medical organization. To the casual observer, the process was open, consultative and scientific.

By 1926, however, it would not be overly cynical to suggest the fix was in. Mental hygiene advocates had, by this point, over three decades of effective agitation and organization in support of the cause. The various church, civic and professional groups who gave evidence before the committee could all be counted on to make the same presentation; each had been effectively lobbied by first, the HCW, then later the League. This fact, coupled with the apparent successes of eugenic measures in other parts of the country, ensured that one position and one position only would be heard before the committee.

Dr. Smith Walker, representing the Nova Scotia Medical Society, "gave figures to show the extent of feeble-mindedness among criminals and degenerates and showed how the public was paying enormous sums for the maintenance of these classes." [80]

Dr. W.H. Hattie, also of the Medical Society and Dalhousie Medical College referred favourably to a student's M.A. thesis whose opinion was that "care" should be provided, "first of all for females of child-bearing age, and especially for those who might be benefited by such training." [81]

Rev. Father MacDonald, professor at Saint Francis Xavier University and special representative of His Lordship the Bishop of Antigonish, "expressed the sympathy of the Antigonish diocese with the work of the commission. Thought that improvements in the country schools would help in some measure. Some of the feeble-minded should undoubtedly be segregated and prevented from propagating their kind." [82]

Miss Catherine Graham of the Graduate Nurses Association of Nova Scotia, "referred to a family containing six childrenóhad been numerous miscarriagesóconditions of this house indescribableóoldest girl of thirteen associating with disreputable colored people. Considered that it was a blot on the community that nothing had been done for the feeble-minded." [83]

Mrs. Agnes Dennis, representing the National Council of Women and the Victorian Order of Nurses commented that, "in making an investigation at the City Home at Halifax it was found that there had been twenty children born of nine feeble-minded mothers ... the Victorian Order of Nurses were continually called upon to go into homes where there are feeble-minded persons and that the nurses find that the spread of communicable diseases in these families cannot be readily prevented. They not only spread disease in the family but outside because they will not follow instructions." [84]

Mrs. Marion S. Morrow of the I.O.D.E. revealed she, "visited many parts of the Nova Scotia where there are terrible cases of feeble-mindedness. Knew of one feeble-minded woman who had eighteen illegitimate children, all of whom were feeble-minded." [85]

To be sure, the survey conducted by Clarence Hincks of the CNCMH at the invitation of the provincial government was the evidential backbone of the 1926 Royal Commission. [86] The province's schools, institutions and homes for mental defectives were studied to provide a more precise account of the incidence of feeble-mindedness in Nova Scotia. [87] Hincks' findings had confirmed the following: "The survey of the province revealed that although the percentage of feeble-minded among adults was roughly one-sixth of one percent, that of the children revealed an alarming rate of three per cent." [88] He also discovered:

Three families that can compare with the notorious Kallikak family described by Dr. H.H. Goddard, were found in Nova Scotia. One of the three has been studied carefully and the following facts are interesting: A man married a feeble-minded girl in 1783 and 570 descendents have been traced. Members of the family living at the present time in one section of the province include 25 feeble-minded, 41 cases of illegitimacy, 9 who have received penitentiary sentences, 7 who have been sent to jail and 3 to reformatories; ten families have received public relief over considerable periods of time and many others are living in dilapidated hovels." [89]

Canada's most influential eugenics lobby had spoken; unless Nova Scotia undertook effective mental hygiene measures, the feeble-minded would continue to reproduce their kind at "an alarming rate". [90]

Hincks was the logical choice for such an undertaking having done similar surveys in several other provinces. But Hincks was in no way a disinterested party in the process. Canada's foremost proponent of sterilization and segregation of the "unfit" could be counted on to confirm the existence of the menace under the guise of scientific objectivity. The question had never been one of the "possible" existence of the feeble-minded among us, but rather the extent of their "ever-increasing" numbers.

IV. Legislation

In 1927, the Rhodes government moved quickly to implement the recommendations of the Royal Commission, and, by so doing, became one of Canada's few governments to give eugenic doctrine a legislative form. Bills 64, 70 and 84 were all enacted to amend the Children's Protection [91], Poor Relief [92] and Education Acts [93], respectively. Also, Bill 174 was enacted to establish the only "training school" east of Orillia, Ontario.

The Nova Scotia Training School finally opened in November, 1929 and was modelled on the infamous Wrentham and Fernald State Schools in Massachusetts. [94] Dr. Prince, in his oration at the founding of the school, made the following point:

The maximum admission to any training school, it is now believed, will never be more than one in every thousand population. So that this Brookside campus planned for an eventual village of six hundred children, should meet the needs of the province of Nova Scotia for a long time to come. [95]

It must have been quite sobering to realize that zero-point-one per cent of the population had the potential to "sap the roots of civilization itself", but as Dr. Prince reminded his listeners:

[It] must never be forgotten that this undertaking is as much in the interests of society as it is for the protection and welfare of the unfortunates themselves. If it costs something to have an institution such as this, it costs infinitely more not to have it, for so great are the social dangers of mental defect, so interwoven is it with disease, dependency, delinquency, and other social ills, that to continue to neglect it in this province is not only an economic error, but it is to reap a crop of thorns and thistles which will be a blight upon the province for all time. [96]

Section eight of the Nova Scotia Training School Act [97] gave the board unlimited power to commit any child who fit the "criteria" of a mental defective, permitting it to "keep and detain or cause to be kept or detained, for the purposes herein, any defective child committed to such training school under the provisions of any Act or Statute of the Province." The definition of "defective child" in section two of the Act refers the reader to another new piece of legislation.

The Children's Protection Act was amended in 1927 to include a new section, Part VI, which outlined a detailed criteria of the different categories of mental defect known to social engineers. Dividing "mentally defective" children into "idiots", "imbeciles" and "morons", the legislation lifted word for word the language and categories of England's notorious Mental Deficiency Act of 1913, and inserted it into provincial legislation. It is at this very moment that eugenic categories were enshrined in Nova Scotian law. Remarkably, these categories remained law until 1961 when three words were severed and replaced with "severely", "moderately" and "mildly" retarded. Only in 1976 when the Children's Services Act came into being was the entire section done away with entirely.

Conclusion

It is not difficult to imagine the pride that comes with having finally achieved what one has dreamed of for decades. Speaking at an annual meeting of the Nova Scotia Society for Mental Hygiene the day before the cornerstone was laid, Dr. Prince was glowing in his appraisal:

We are turning a new page in our book of golden days. There is a spell upon us and about us, which is more than the spell of autumn. It is like the night before Christmas. It is like the denouement of a beautiful story. For at last all is in readiness for the silver trowel, when a few hours hence there shall be well and truly laid the corner stone of the new Brookside school, which to bring into being this society was born. [98]

As the history of eugenic social policy has demonstrated, one person's beautiful story is always someone else's nightmare. Hundreds of "worse than worthless" children were herded into this institution to save the rest of society from ruin. Not one of their names is known. Compounding the problem is the fact that this disturbing chapter of our history has all but disappeared from the history books, if it was ever there in the first place.

Where there is oppression, there are always victims. The scapegoats in this eugenic crusade were the children. In fact, it is likely that thousands of children passed through the doors of the Brookside Training School, branded with the stigma of mental defect and treated as the "waste products" they were perceived to be. One thing is certain: Nova Scotia must atone for the violence committed against these helpless children.

Disturbing still is the fact that by the time Alberta, British Columbia and Nova Scotia had drawn up legislation to eradicate mental defectives from society, eugenics as a scientific doctrine had largely been discredited. [99] By 1926, one of the main architects of the Nova Scotian eugenics movement, Ernest H. Blois, in a paper read before the Annual Conference of Children's Aid Societies drops the following bombshell:

[W]e were told once that most crimes, sexual immorality, especially among females, and evil in many forms were due largely to feeble-mindedness. This we now know to be untrue, but nevertheless, in dealing with these particular forms of vice and crime, feeble-mindedness is one, and in some cases a very large factor in a very complex problem. [100]

Yet, he still argued for their incarceration. One of the conclusions from the 1926 Royal Commission included the incredible statement, "too little is known regarding the hereditary nature of feeble-mindedness". [101] They, too, argued for confinement. How the eugenic argument survived without its main theoretical support remains a mystery.

A look at the historical facts from across the continent shows that eugenics left no territory untouched. It was perhaps a movement that seemed impeccable in its logic and unstoppable in momentum. After all was said and done, the victims paid the price and the "progressives" went on with their lives as if nothing had happened. [102]

Appendix 1

Confidential notes for social workers and welfare agencies in connection with the survey of mental deficiency in Nova Scotia.

The survey staff would appreciate the names, ages and addresses of mentally deficient individuals who fall into the classes 1 to 8 outlined in the next paragraph. In connection with the names presented notes should be appended giving evidence of mental deficiency together with showing in what way the case is a social problem.

The following eight types of mental deficiencies are of interest to the survey staff.

1) Feeble-minded children of school age who can be trained with profit in special classes in the public school system. These children have IQ's of between 50 and 75; they have no ingrained anti-social traits and they come from reasonably good homes.

2) Feeble-minded children of the moron type (IQ between 50 and 75) who have pronounced anti-social traits or grave personality defects and who, though trainable, are unsuited to special class instruction in public schools.

3) Children of the moron type who, because of unsatisfactory home conditions are unsuited for special class instruction in public schools.

4) Middle and high grade imbecile children (IQ 25-50) who are trainable in an institution but unsuited for instruction in special classes in public schools.

5) Idiot and low grade imbecile children (IQ less than 25) who are more or less helpless but who can be trained to a degree in habits of cleanliness and self-help in an institution.

6) Mentally deficient girls of high grade imbecile or moron type -- girls of child-bearing age who have immoral sexual tendencies and who require institutional training.

7) Mentally deficient adults both male and female who are dependant on society for support.

8) Mentally deficient adults both male and female who come to the notice of the state because of delinquent acts.

(Appendix 1 cont'd)

NOTE: - The record card contains spaces for such information as - name, age, date, address, referred by, data suggesting mental deficiency and data concerning the case as a social problem. The way in which the card can be used is illustrated by the following notes on a hypothetical case: -

Name; Miss Jennie Smith Age; 22 Date; Nov. 1st, 1926

Address; 10 Park St, referred by; Miss A. Jones,

Halifax C.A.S. Halifax.

Date suggesting mental deficiency; Jennie Smith was a failure at school. She did not get further than the third grade. As a child she was considered dull and stupid. Those who know her now realize that she is lacking in judgement and easily imposed upon. In talking she has a silly inconsequential grin.

Data concerning the case as a Social Problem; - This girl gets temporary employment as a house maid. She never holds a position for any length of time. She has given birth to one illegitimate child and it is feared that she is again consorting with men.

Bibliography

Monographs, papers and journals

Blois, Ernest H. The Mentally Deficient as a Social Problem (C.A.S: 1926), N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14757.

Callinicos, Alex. Social Theory: An Historical Introduction (NYU Press: New York, 1999)

Canadian Mental Health Association. Milestones in Mental Health, 1962, N.S.A.R.M., v/f v.301 #6

Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene. "Mental Hygiene Survey of the Province of Nova Scotia", Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene, v.3, no.1, April, 1921, N.S.A.R.M., v/f v.372 #25.

Hatfield, Lorne. Sammy the Prince (Lancelot Press: Halifax, 1990)

Hattie, W.H. "The Prevention of Insanity", Maritime Medical News, v.16, Feb 04, no.2, pp.44-47.

---------------. National Health, the Nation's Greatest Asset (Department of Public Works: Halifax, 1909)

---------------. "The Prevention of Insanity", Canadian Medical Association Journal, v.1 no.11, November, 1911, pp. 1118 -- 1024.

---------------. "The Physician's Part in Preventing Mental Disorder", Public Health Journal, v. 11, 1920, pp. 315-320.

---------------. "The Coordination of State and Private Enterprises in Public Health Work", Public Health Journal, v. 11, 1920, pp. 418 -- 421.

---------------. "Sanitation", Public Health Journal, v. 11, 1920, pp. 207 -- 21.

---------------. "What Does Public Health Administration Embrace?", Canadian Medical Association Journal, v.11, 1920, pp. 900-903.

---------------. "Mental Hygiene -- part 1", Nova Scotia Medical Bulletin, v.9, no.2, February, 1930, pp.75-79.

Hincks, Clarence M. "Recent Progress of the Mental Health Movement in Canada", Canadian Medical Association Journal, v.11, Jan. 1921, pp. 822-825.

MacKinnon, Fred R. The Life and Times of Ernest Blois (Senior Citizen's Secretariat: Halifax, 1992)

MacMurchy, Helen. The Almosts: A Study of the Feeble-Minded (Riverside Press: Boston, 1920)

-----------------------. Organization and Management of Auxiliary Classes (J.K.Cameron: Ontario, 1915)

McLaren, Angus. Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945 (McClelland & Stewart: Toronto, 1990)

Merrill, Maude. "Feeble-Mindedness and Crime: The Descendents of Jasper Bar" Dalhousie Review, v.1, no.4, Jan. 22, p.360 - 365.

Prince, Samuel H. "Mental Hygiene -- part 2", Nova Scotia Medical Bulletin, v.9, no.2, February, 1930, pp. 126-131.

Prince, Samuel. The Social System: a Compendium of Popular Sociology (Ryerson Press: Toronto, 1958)

Pringle, Heather. "Alberta Barren" Saturday Night, June, 1997. Vol.112, no.5; pp. 30-40.

Reid, Alexander P. Stirpiculture and the Ascent of Man (T.C Allen: Halifax, 1890)

--------------------. "Eugenics: The Sordid, Scientific Side or Life", Public Health Journal, v.4 (1913) pp.284-286.

Russell, James. "Is The Anglo-Saxon Race Degenerating?" Canadian Practitioner and Review, August, 1900.

Schiller, F.C.S. "The Case for Eugenics", Dalhousie Review, v.4, No.4 Jan.25 p.405 - 410.

Newspapers

"Class of Unfortunates Worth Looking After" The Echo, Saturday, February 29, 1908.

"Care of the Feeble-minded" The Echo, Saturday, March 7, 1908.

"Canada Should Have Uniform Health Laws" The Echo, Friday, October 5, 1917.

"The City's Welfare" , The Echo, February 16, 1918.

"Care of the Feeble-Minded: A Present Day Problem", The Mail, Saturday, March 7, 1908.

"Nova Scotia is Doing Nothing for Feeble-Minded Among Its Population", The Mail, Saturday, March 14, 1908.

"Ninety-One Mentally Defective Children Enrolled in Our Schools, Teachers Report" Editorial - The Mail, Saturday April 1, 1911.

"The Care and Training of the Feeble-Minded in This Community", The Mail, Friday, November 17, 1911.

"Why Not Do Something for the Feeble-Minded?" The Mail, December 5, 1917.

"The Feeble-Minded", The Recorder, March 9, 1908.

Other

Department of Public Health Bulletin, "Is the Mentally Defective a Problem in Preventive Medicine?" - (monthly) Toronto, N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14723.

Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene Mental Hygiene Bulletin, February 20, #1, N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14723.

First Annual Report of the Nova Scotia Training School (Province of Nova Scotia: 1929)

Halifax Local Council of Women -- minutes, N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 9596

National Council of Women of Canada, "Lovest Thou Thy Land?" brief prepared in support of a Royal Commission on Mental Deficiency in Canada -- N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14723.

National Council of Women of Canada, "Mental Hygiene in Nova Scotia", December 21, 1929, N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 9596.

Nova Scotia Society for Mental Hygiene, - minutes - N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14757.

Report Respecting Feeble-Minded In Nova Scotia, Journals and Proceedings of the House of Assembly, 1917, Part 2 (Commission of Public Works and Mines: Halifax, 1918)

Report of the Royal Commission Concerning Mentally Deficient Persons in Nova Scotia, Hon. W.L. Hall, chair (Halifax, 1927)

Court Decisions

Re Eve, [1986] 2 S.C.R. 388.

Muir v. Alberta (1996), 132 D.L.R. (4th) 695.

Legislation

The Children's Protection Act, R.S.N.S. 1923, c. 166, as am. by S.N.S, c. 43.

The Education Act, R.S.N.S. 1923, c.60, as am. by S.N.S. 1927, c.2.

Nova Scotia Training School Act, S.N.S. 1927, c.5.

The Poor Relief Act, R.S.N.S. 1923, c.48, as am. by S.N.S. 1927, c.21.

Endnotes

1 The Nova Scotia Medical Bulletin, v.9, no.2, February 1930, p.85

2 Hatfield, Lorne. Sammy the Prince (Lancelot Press: Halifax, 1990) p.155

3 "Nova Scotia is Doing Nothing for Feeble-Minded Among Its Population", The Mail, Saturday, March 14, 1908.

4 Red Deer was the site of the provincial training school (PTS) that had sterilized Leilani Muir. See Muir v. Alberta (1996), 132 D.L.R. (4th) 695.

5 Prince, Samuel quoted in First Annual Report of the Nova Scotia Training School (Province of Nova Scotia: 1929) p.28

6 Prince, Samuel H. "Mental Hygiene -- part 2", Nova Scotia Medical Bulletin, v.9, no.2, February, 1930, p. 129

7 Prince, Training School, p.27

8 Report of the Royal Commission Concerning Mentally Deficient Persons in Nova Scotia, Hon. W.L. Hall, chair (Halifax, 1927) p.40

9 Galton Francis. "Hereditary Talent and Character" quoted in Callinicos, Alex. Social Theory: An Historical Introduction (NYU Press: New York, 1999) p. 107

10 Callinicos, Alex. Social Theory: An Historical Introduction (NYU Press: New York, 1999) p. 108

11 McLaren, Angus. Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945 (M & S: Toronto, 1990) p.24

12 Ibid., p.14

13 Merrill, Maude. "Feeble-Mindedness and Crime: The Descendents of Jasper Bar" Dalhousie Review, v.1, no.4, Jan. 22, p.360

14 Ibid., p.361

15 Reid, Alexander P. "Eugenics: The Sordid, Scientific Side or Life", Public Health Journal, v.4 (1913) pp.284

16 Schiller, F.C.S. "The Case for Eugenics", Dalhousie Review, v.4, No.4 Jan/25 p.409

17 Ibid., p.406

18 McLaren, Our Own, p.169

19 Pringle, Heather. "Alberta Barren", Saturday Night, June, 1997. Vol.112, no.5, p. 40

20 McLaren, Our Own, p.169

21 Ibid., p.170

22 Ibid., p.90

23 Report Respecting Feeble-Minded In Nova Scotia, Journals and Proceedings of the House of Assembly, 1917, Part 2 (Commission of Public Works and Mines: Halifax, 1918)

24 Report of the Royal Commission Concerning Mentally Deficient Persons in Nova Scotia, Hon. W.L. Hall, chair (Halifax, 1927)

25 Ibid., p.41

26 Schiller, "Eugenics", p.410

27 McLaren, Our Own, p.166

28 Russell, James. "Is The Anglo-Saxon Race Degenerating?", Canadian Practitioner and Review, August, 1900, p.12

29 Ibid., p.12

30 MacMurchy, Helen. The Almosts: A Study of the Feeble-Minded (Riverside Press: Boston, 1920) p.173

31 MacMurchy, Helen. Organization and Management of Auxiliary Classes (J.K.Cameron: Ontario, 1915) p.25

32 Ibid., p.2

33 Ibid., p.3

34 McLaren, Our Own, p.37

35 National Council of Women of Canada, "Lovest Thou Thy Land?", brief prepared in support of a Royal Commission on Mental Deficiency in Canada -- N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14723.

36 Department of Public Health Bulletin, "Is the Mentally Defective a Problem in Preventive Medicine?" - (monthly) Toronto, Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management (hereafter N.S.A.R.M.), MG 20, micro. 14723.

37 Ibid.

38 Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene - Mental Hygiene Bulletin, February 20, #1, N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14723.

39 Ibid., p.12

40 Ibid., p.11

41 Ibid., p.14

42 McLaren, Our Own, p.27

43 Reid, Alexander P. Stirpiculture and the Ascent of Man (T.C Allen: Halifax, 1890) p.5

44 Ibid., p.6

45 Reid, Alexander P. "Eugenics: The Sordid, Scientific Side or Life", Public Health Journal, v.4 (1913) p. 286

46 Ibid., p.285

47 Ibid., p.286

48 Hattie, W.H. "The Prevention of Insanity", Maritime Medical News, v.16, Feb 04, no.2, p.45

49 Ibid., p.47

50 Hattie, W.H. "The Prevention of Insanity", Canadian Medical Association Journal, v.1 no.11, November, 1911, p. 1022

51 Hattie, W.H. "The Physician's Part in Preventing Mental Disorder", Public Health Journal, v. 11, 1920, pp. 316

52 Ibid., p.319

53 Hattie, W.H. "Sanitation", Public Health Journal, v. 11, 1920, p. 207

54 Hattie, W.H. "Prevention", (1904), p.45

55 McLaren, Our Own, p.24

56 Prince, Training School, p.28

57 MacMurchy, Helen. Auxiliary Classes, p.11

58 "Class of Unfortunates Worth Looking After", The Echo, Saturday, February 29, 1908.

59 Prince, Training School, p.28

60 "Canada Should Have Uniform Health Laws", The Echo, Friday, October 5, 1917.

61 "Care of the Feeble-Minded: A Present Day Problem", The Mail, Saturday, March 7, 1908.

62 "Nova Scotia is Doing Nothing for Feeble-Minded Among Its Population" The Mail, Saturday, March 14, 1908.

63 "Care of the Feeble-minded", The Echo, Saturday, March 7, 1908.

64 "The City's Welfare", The Echo, Feb.16, 1918.

65 "Why Not Do Something for the Feeble-Minded?", The Mail, December 5, 1917.

66 Report Respecting Feeble-Minded In Nova Scotia, p.3

67 "The Feeble-Minded", The Recorder, March 9, 1908

68 "The Care and Training of the Feeble-Minded in This Community", The Mail, Friday, November 17, 1911.

69 Halifax Local Council of Women -- minutes, N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 9596

70 Prince, Training School, p.29

71 Nova Scotia Society for Mental Hygiene - minutes - N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14757

72 Ibid.

73 Halifax Local Council of Women -- minutes, December 18, 1912. See also Nova Scotia Society for Mental Hygiene - minutes, December 2, 1912.

74 Report Respecting Feeble-Minded, p.8; Report of the Royal Commission, p.42

75 Report Respecting Feeble-Minded, p.8; Report of the Royal Commission, p.32

76 Report Respecting Feeble-Minded, p.8

77 Report of the Royal Commission, p.37

78 Ibid., p.38

79 Ibid., p.32

80 Ibid., p.26

81 Ibid., p.25

82 Ibid., p.24

83 Ibid., p.21

84 Ibid., p.20

85 Ibid., p.18

86 History sometimes provides interesting parallels. The Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene was the forerunner to today's Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) and the League is the parent of the Nova Scotia Division of the CMHA. The CMHA website makes no mention of its long eugenic pedigree.

87 See appendix 1 for the criteria devised for identifying the feeble-minded - N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14757.

88 Hincks accounted for the unusually high rate of feeble-mindedness among children by highlighting the fact that Nova Scotia had experienced an abnormal rate of emigration of its better stock to the U.S. Report of the Royal Commission, p.36

89 Report of the Royal Commission, p.32

90 Ibid.

91 The Children's Protection Act, R.S.N.S. 1923, c. 166, as am. by S.N.S, c. 43.

92 The Poor Relief Act, R.S.N.S. 1923, c.48, as am. by S.N.S. 1927, c.21.

93 The Education Act, R.S.N.S. 1923, c.60, as am. by S.N.S. 1927, c.2.

94 Prince, Training School, p.23

95 Prince, Training School, p.26

96 Ibid.

97 Nova Scotia Training School Act, S.N.S. 1927, c.5.

98 Prince quoted in the Nova Scotia Medical Bulletin, v.9, February 1930, p.146

99 Pringle, Heather. "Alberta Barren", Saturday Night, June, 1997. Vol.112, no.5; pp. 30-40.

100 Blois, Ernest H. The Mentally Deficient as a Social Problem (C.A.S: 1926), N.S.A.R.M., MG 20, micro. 14757

101 Report of the Royal Commission, p.42

102 The only participant to have shown anything resembling remorse for the past is Mr. Blois. During an address to children's aid conference delegates in June 1946, Blois assessed the lessons of the past:

As workers let us rid ourselves of false claims to knowledge which we do not possess. Let us be less conceited and more humble in the presence of truth. We have been too eager to follow new and strange gods -- to mistake the slogan for the battle ... One thing we definitely need at this time and that is more exact knowledge. There is far too much taken for truth because someone, often of little importance and less knowledge, said it was true. We require scientific study of many matters about which we know very little but what we are told by someone who arrived at that particular conclusion without careful and scientific study of sufficient facts to warrant a worthwhile opinion, much less the laying down of a basic rule. See MacKinnon, Fred R. The Life and Times of Ernest Blois (Senior Citizen's Secretariat: Halifax, 1992)

|